A fake Dior bag, even one you know is fake, can still provide a little pleasure. Why? It looks nice. And it holds within it the comfort of the familiar and the aspired-to.

This first occurred to me last year, thousands of miles from Dior’s Paris and New York’s Chinatown, when I laid eyes on Bangladesh’s fake Taj Mahal.

The fake Taj is a tribute to a tribute. A souvenir snow globe for a country that has never seen snow.

Bangladesh is starving for entertainment. The perspiring capital, Dhaka, is home to a couple dreadful amusement parks that cater to the rich, a dreadful zoo where the poor animals keep dying and a number of old-fashioned movie halls that middle-class people won’t be caught dead visiting because of their reputation as masturbatoriums.

The city’s lovely botanical garden is one of only a few parks and developers are planning to bisect it with a slurry pipeline so they can fill a nearby riverbank and build apartment towers.

There isn’t much to do when the day’s labors are finished but watch TV, play cricket and gossip.

The boredom has grown worse in the last decade as Bangladesh’s economy has taken off, depositing new spending money in the pockets of millions of people who previously couldn’t spare a cent.

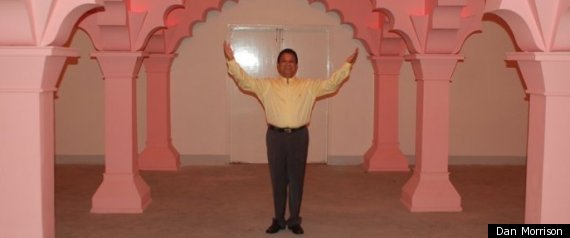

Into this vacuum stepped film producer Ahsanullah Moni, a silver-tongued captain of industry and illusion. In 2008, newswires on four continents lit up with the story that Moni was building a replica of the Taj Mahal on a plot of farmland outside Dhaka.

The real Taj Mahal, of course, resides 800 miles and one trigger-happy border away, in the north Indian town of Agra. The Mughal emperor Shah Jahan built it as a mausoleum for one of his wives, the empress Mumtaz Mahal, who died giving birth to their 14th child. It took 20,000 workers more than 20 years to complete the original Taj Mahal.

Ahsanullah Moni didn’t have that kind of time or manpower.

His Taj would be built using modern methods and cost $58 million, reported a raft of credulous foreign publications, including The Times of London, Reuters, the BBC, and the Guardian. The marble, from Italy, would be of a quality surpassing that of its inspiration, Moni bragged. Critics complained of the price tag. The Indian embassy made peevish noises about copyright infringement. And the story faded from view.

Last year, accompanied by Schon Bryan, my boon companion in the book The Black Nile, I took a drive through Dhaka’s apocalyptic traffic, past hazy green fields of rice paddy, into the countryside district of Sonargaon to see Moni’s Taj.

And it was lovely.

It was no less lovely for looking nothing like the real Taj Mahal. In size and proportion the attraction bears only a slight resemblance to the Indian wonder, as if made from a sketch or a decade-old memory. It might have cost $58,000 to build.

The central structure and its four minarets were obviously clad in bathroom tiles, some in floral patterns of pink, amber, and lilac. The Belgian diamonds Moni had spoken of had apparently been replaced by plastic. Inside, where, in the real Taj, women pray over the tomb of Mumtaz Mahal, was a raw chamber filled with construction debris.

It didn’t matter.

“How am I supposed to see the real Taj Mahal?” asked Shahidul Haque, 40-year-old a truck driver. “It would cost a fortune to fly my family to India, and we’d never get visas anyway.”

“I’ve seen pictures of the Indian Taj, and this is pretty close,” Haque added. “We’re a poor country.”

Moni, however, is blind to the project’s shortcomings, insisting that “It is a 100 percent accurate replica.”

The man has more than a little P.T. Barnum in him, not to mention Frederic Thompson and Elmer “Skip” Dundy, the early 20th-Century founders of Coney Island’s Luna Park.

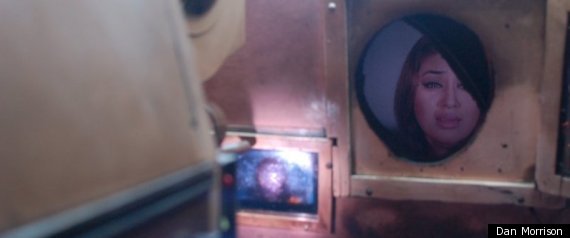

Back in Dhaka, he gave Schon and me a tour of the movie theater that doubles as his headquarters and production studio. A Shah Jahan biopic was in the works, he said, to be filmed on location at the new Taj and in the theater’s basement, which had been painted pink for the bedroom scenes.

But the Taj was just the beginning. “I want a complex,” Moni said, pointing us to models of a three-sided pyramid and a giant duck that would one day stand beside the porcelain monument in Sonargaon.

A veteran of Bangladesh’s bloody 1971 war of independence, Moni is a patriot whose desk holds a photo-shopped picture of himself standing with the country’s founding father. He is intimately familiar with the fantasies of his people.

“I will build a pyramid bigger than the one in Egypt,” Moni said with a grin. “It will be my next gift to Bangladesh.”

—

Dan Morrison’s reporting has taken him from BBQs with the Latin Kings street gang to ride-alongs with the police assassins of Bombay. He is author of The Black Nile, an account of his 3,600-mile journey down the Nile River through Uganda, Sudan, and Egypt, published by Viking Penguin.

(This piece first appeared in the Huffington Post on August 21.)